A five-step guide to knowing, understanding and making drinks with the grain. By Jethro Kang.

We’ve been mining medicine forever for things to get a buzz on (see bitters, wine and whisky). Here’s another for the list: Job’s Tears, a grain that’s traditionally consumed in East Asia for its medicinal properties. Doesn’t hurt that it tastes good too. From its classic serve as a sweet soup to its use as a sweetener in cocktails today, here are five things you should know about Job’s Tears.

It’s a grain.

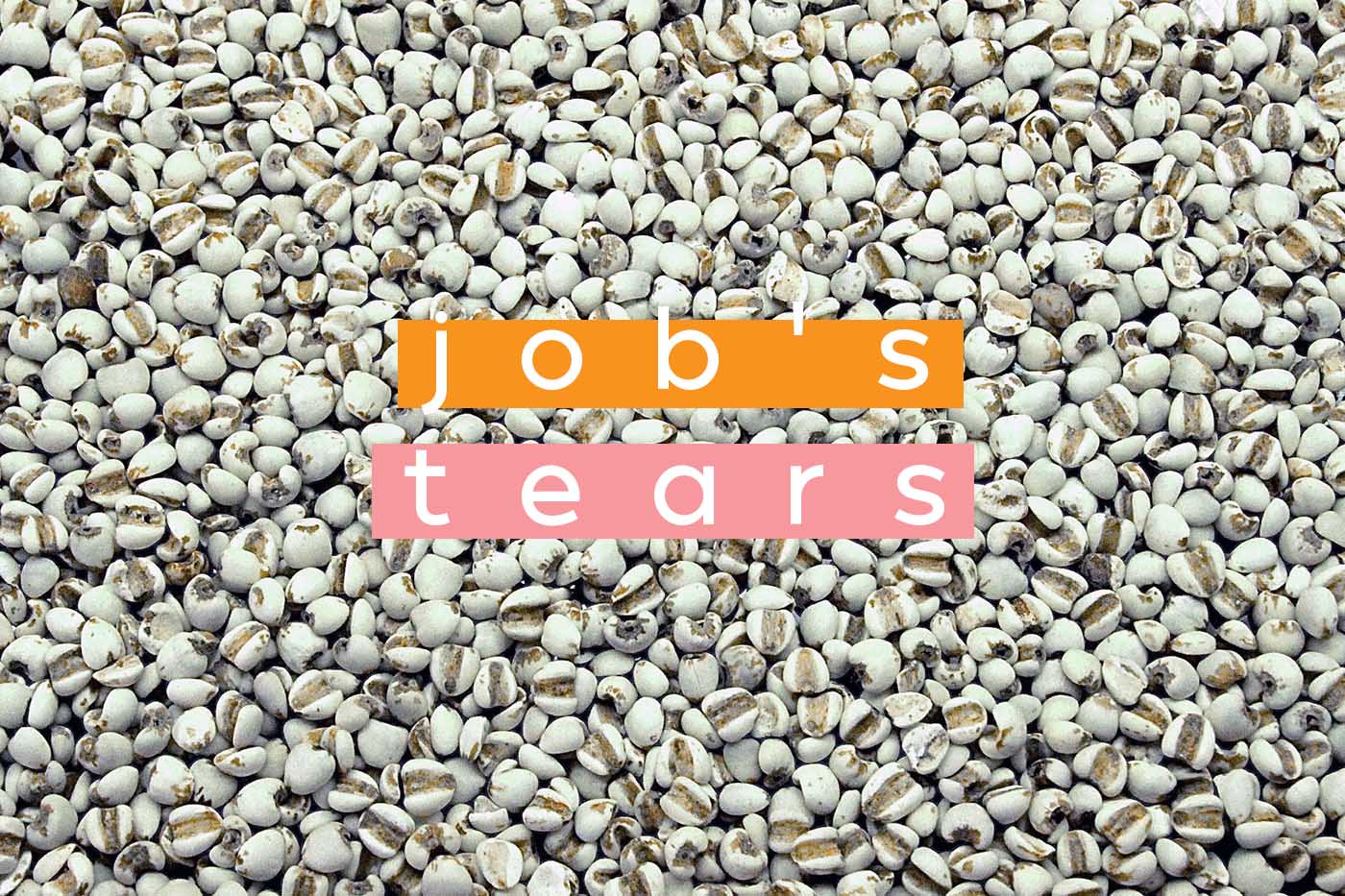

Job’s Tears is a cereal plant native to Southeast Asia. The edible part is its soft-hulled grain, which is dried before being sold. There’s another hard-shell variety that’s used to make jewellery, but we can’t eat it, so let’s ignore that.

It goes by many names.

Job’s Tears, Chinese pearl barley or coix seed. Also, yulmu in Korean, yi mi in Mandarin, hato mugi in Japanese and coix lacryma-jobi in geek-speak. In Singapore and Malaysia, they’re sometimes mistakenly sold as a drink called “barley water” (it’s not actually barley). Whatever its name, it’s round, white, with a light brown groove on one side. Slightly smaller than a pistachio.

It’s used as a remedy.

In traditional Chinese medicine, Job’s Tears is thought of having cooling and diuretic effects. It reduces inflammation, swelling, pus build-up and congestion, and is prescribed for eczema, diarrhoea and sometimes even cancer. Today, it’s growing fashionable among the health-food crowd for being gluten-free and as an alternative grain.

It’s delicious.

More importantly, Job’s Tears tastes good. In Chinese cuisine, it’s simmered with water and sugar to make a cloudy drink that’s creamy, nutty and sweet. “It’s slightly lactic from the stewing with sweet grain notes,” says Matthew Hall of Hakkasan Shanghai, who uses the same technique to make a syrup. In Korea, it’s roasted, pulverised and brewed into a thick tea, almost like oatmeal. People in Southern China, Hong Kong and Vietnam serves it chilled as a dessert soup. The Thais have it with soy or coconut milk, while the Japanese turn it into vinegar.

It gets you drunk too.

Trust our ancestors to ferment anything starchy. As scientists recently discovered in an archaeological dig in Shaanxi, people were brewing beer 5,000 years ago using broomcorn millet, barley, tubers and Job’s Tears. Another tradition sees it being distilled it into something similar to baijiu in China or soju in Korea. Today, bartenders like Hall are using them to sweeten cocktails like the Coix Solero. “I found it works well with light citrus, soft fruits and coconut,” he says, and adds peach and pomegranate to the sake-based drink.

As for old beer, Beijing brewers Jing-A and Moonzen from Hong Kong collaborated on a re-creation they called the Mijiaya Neolithic Ale. Made only from ingredients available during the Yangshao period (there weren’t any hops around), it “has an effervescent lemon tartness that cuts through the sweet and earthy flavours of its ancient fermentables.

Recipes (Click to view)

Coix Solero